Australian journal of general practice

-

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are a vulnerable population who have been exposed to high work-related stress during the COVID-19 pandemic because of the high risk of infection and excessive workloads. HCWs are at greater risk of mental illness, particularly sleep disturbances, post-trauma stress syndromes, depression and anxiety. ⋯ Opportunistic screening for mental health issues among HCWs is especially important during the current pandemic. Various tools and strategies can be used for efficient assessment and treatment of the common mental health issues HCWs are likely to face.

-

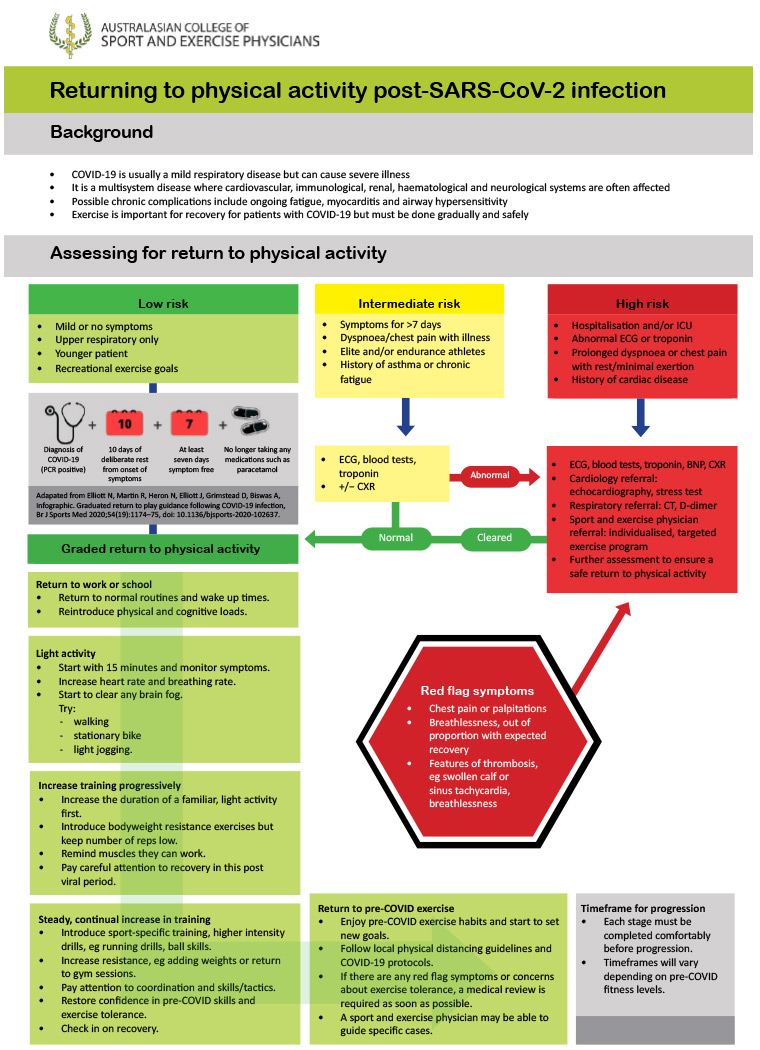

Jewson, McNamara & Fitzpatrick describe a roadmap for return to activity after COVID infection, developed by the Australasian College of Sport and Exercise Physicians.

They consider three risk categories:

Low: Under 50 years with mild illness resolving within 7 days.

Intermediate: prolonged symptoms (>7d); persistent SOB or chest pain; pre-existing comorbidities; elite/endurance athletes.

- Consider ECG & baseline pathology, including troponin.

High: hospitalised with COVID; SOB or chest pain at rest; cardiac abnormalities.

- Multi-disciplinary team to advise & monitor return to exercise.

Graded return to physical activity

- Begin after 10 days of rest and when 7 days symptom-free.

- Begin with 15 minutes of light activity, with gradual increase guided by lack of fatigue with activity.

- 🚩Red flag symptoms: chest pain, palpitations, severe dyspnoea. STOP & medical review.

Return to exercise flowchart:

summary -

SARS-CoV-2 is known to cause milder disease in children when compared with adults, but the extent of this is unclear. The aim of this article is to estimate the case fatality rate (CFR) for SARS-CoV-2 infection and SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in young children aged <5 years, and compare this with estimated CFRs for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza. ⋯ SARS-CoV-2 infection is likely to be less lethal than RSV in children aged <5 years, but more lethal than influenza.

-

The availability of a COVID-19 vaccine is being heralded as the solution to control the current COVID-19 pandemic, reduce the number of infections and deaths and facilitate resumption of our previous way of life. ⋯ While a number of vaccines are currently under development, with at least seven undergoing phase III trials (28 August 2020), it is hoped that an effective COVID-19 vaccine will become available to the public in 2021. Ensuring public confidence in vaccine safety and effectiveness will be crucial to facilitate uptake. General practitioners are at the forefront of public health, and one of the most trusted sources for patients. In this article, the authors discuss the expedited vaccine development process for COVID-19 vaccines; the likely vaccine prioritisation schedule and anticipated key target groups; the behavioural and social drivers of vaccination acceptance, including the work required to facilitate this; and the implications for general practice.

-

Patients with red eyes frequently present to general practitioners (GPs). Although infrequent, some patients with COVID-19 may present with features typical of viral conjunctivitis. SARS-CoV-2 is expressed at a low rate in tears, which may be a source of infection to GPs caring for patients at high risk of COVID‑19. ⋯ It is important that GPs: 1) have a high index of suspicion that patients with apparently typical viral conjunctivitis may have an uncommon presentation of COVID-19 illness, 2) develop appropriate telephone triage systems to reduce patient consultations, and 3) foster relationships with their ophthalmologist and optometrist colleagues who can provide phone advice, guidance on treatment initiation and definitive care when necessary.